Dictablanda Of Dámaso Berenguer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Dictablanda'' of Dámaso Berenguer, or Dámaso Berenguer's dictatorship (''

The ''Dictablanda'' of Dámaso Berenguer, or Dámaso Berenguer's dictatorship (''

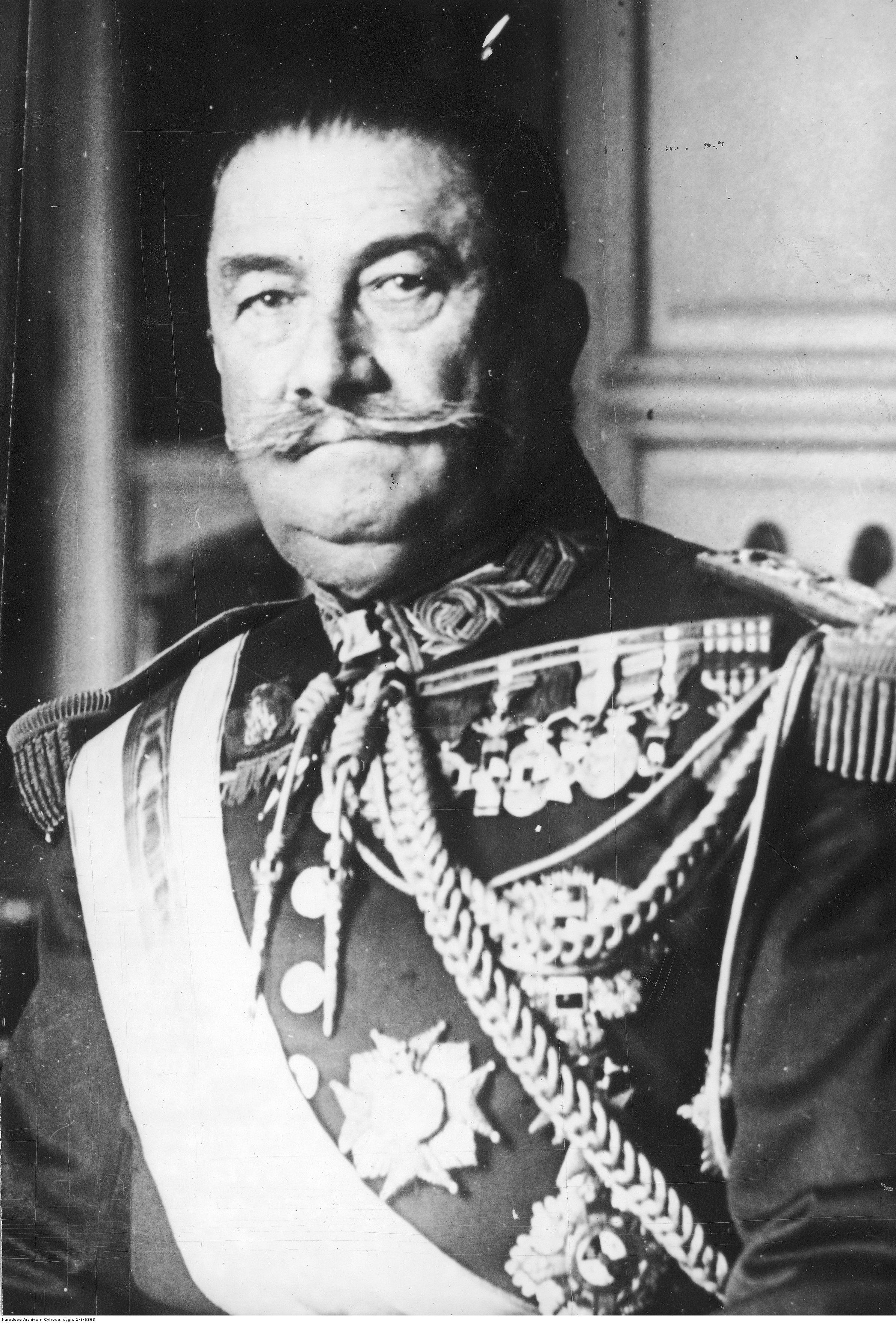

On 13 February 1931 King Alfonso XIII ended General Berenguer’s dictablanda and named Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar new president. At the time Aznar was sardonically described as “from the Moon politically and , from Cartagena geographically”, due to his minor political importance. Alfonso XIII had previously offered the post to liberal Santiago Alba and the “constitutionalist” conservative

On 13 February 1931 King Alfonso XIII ended General Berenguer’s dictablanda and named Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar new president. At the time Aznar was sardonically described as “from the Moon politically and , from Cartagena geographically”, due to his minor political importance. Alfonso XIII had previously offered the post to liberal Santiago Alba and the “constitutionalist” conservative

The ''Dictablanda'' of Dámaso Berenguer, or Dámaso Berenguer's dictatorship (''

The ''Dictablanda'' of Dámaso Berenguer, or Dámaso Berenguer's dictatorship (''dictablanda

''Dictablanda'' is a dictatorship in which civil liberties are allegedly preserved rather than destroyed. The word ''dictablanda'' is a pun on the Spanish word ''dictadura'' ("dictatorship"), replacing ''dura'', which by itself is a word meaning ...

'' meaning "soft dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship are ...

" as opposed to ''dictadura'', which means "hard dictatorship") was the final period of the Spanish Restoration and of King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alfo ...

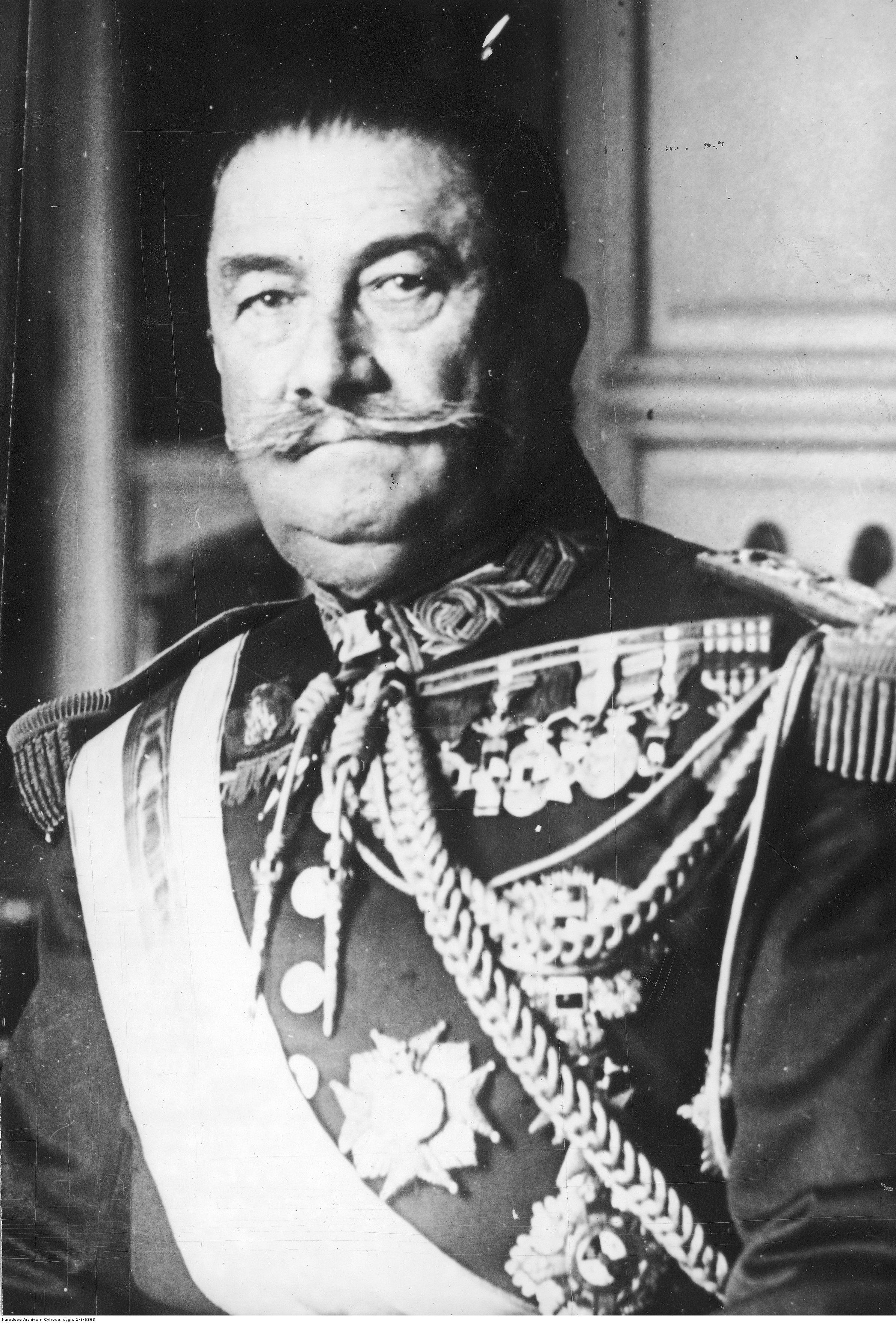

’s reign. This period saw two different governments: Dámaso Berenguer

Dámaso Berenguer y Fusté, 1st Count of Xauen (4 August 1873 – 19 May 1953) was a Spanish general and politician. He served as Prime Minister during the last thirteen months of the reign of Alfonso XIII.

Biography

Berenguer was born in Sa ...

’s government, formed in January 1930 with the goal of reestablishing “constitutional normalcy” following Primo de Rivera Primo de Rivera is a Spanish family prominent in politics of the 19th and 20th centuries:

*Fernando Primo de Rivera (1831–1921), Spanish politician and soldier

*Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870–1930), nephew of Fernando, military officer and dictat ...

’s dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship are ...

, and President Juan Bautista Aznar

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of ''John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanish, t ...

’s government, formed a year later. The latter paved the way to the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

.

The term ''dictablanda'' was used by the press to refer to the ambivalence of Berenguer’s government, which neither continued the model of the former dictatorship nor did it fully reestablish the 1876 Constitution.

The Berenguer error

Alfonso XIII named General Dámaso Berenguer president on 28 January 1930, with the goal of returning the country to “constitutional normalcy”. However, historians have pointed out the impossibility of achieving this by attempting to transition towards a liberal regime by simply reestablishing the political order that existed before the 1923 coup and not considering the link between theCrown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

and Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship. Nonetheless, this mistake was made by the King and his government by trying to bring Spain back to the 1876 Constitution despite it having been abolished for six years. Since 1923, Alfonso XIII had been a king without a Constitution. During that time, his rule was legitimized not by a written document, but by a coup d’état allowed by the King. The Monarchy had become associated with the dictatorship, and it now attempted to survive when the dictatorship had ceased to exist.

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

politicians and “monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

without a King”, as well as numerous jurists, dismissed the return to “constitutional normalcy” as impossible. On 12 October 1930, jurist Mariano Gómez would write: “Spain lives without a Constitution”. According to Gómez, Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship initiated a constituent process that could only be concluded with a return to normalcy through “a constituent government, constituent elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operate ...

presided by a neutral power that wasn’t a belligerent in the conflict created by the dictatorship, a system of freedoms and guarantees for citizens and courts

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance ...

wielding supreme authority to create the new common legality”.

General Berenguer was greatly troubled while articulating his government because the two dynastic parties, the Liberal-Fusionist Party and the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

had ceased to exist following the six-year dictatorship, for they weren’t actual political parties but interest groups whose only objective was to hold power at a certain time, owing to the electoral fraud instituted by the ''cacique'' system. Most politicians refused to collaborate with Berenguer as individuals, so he could only count on the most reactionary sector of conservatism, headed by Gabino Bugallal. Additionally, Patriotic Union, the only political party of the dictatorship, which in 1930 turned into the National Monarchist Union

The National Monarchist Union ( es, Unión Monárquica Nacional, links=no; UMN) was a Spanish political party, founded in April 1930 as successor to the Patriotic Union, the official party promoted by the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. Its leade ...

and was losing members, didn’t support Berenguer’s government either because it opposed the Constitution. As a result, the Monarchy didn’t have at its disposal any political organizations capable of guiding the transition process.

Berenguer's policies did not improve the position of the Monarchy. The slow rate at which the new liberalizing policies were being implemented cast doubt on the government’s claimed objective of reestablishing “Constitutional normalcy”. As a result, the press began to call the new regime “''dictablanda''”, meaning “soft dictatorship”. During this time, some politicians of the two dynastic parties defined themselves as “monarchists without a King” (such as Ángel Ossorio y Gallardo) and others joined the Republican side (such as Miguel Maura

Miguel Maura (1887–1971) was a Spanish politician who served as the minister of interior in 1931 being the first Spanish politician to hold the post in the Second Spanish Republic. He was the founder of the Conservative Republican Party.

Early ...

and Niceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

, both of whom founded the Liberal Republican Right

The Liberal Republican Right (''Derecha Liberal Republicana'') was a Spanish political party led by Niceto Alcalá Zamora, which combined immediately with the incipient republican formation of Miguel Maura just before the Pact of San Sebastián, ...

).

José Ortega y Gasset

José Ortega y Gasset (; 9 May 1883 – 18 October 1955) was a Spanish philosopher and essayist. He worked during the first half of the 20th century, while Spain oscillated between monarchy, republicanism, and dictatorship. His philosoph ...

published an article on 15 November 1930 in the newspaper ''El Sol'' titled "The Berenguer error". It had a significant repercussion and it concluded with the following line: “Spaniards, your State does not exist! Rebuild it! ''Delenda est Monarchia''”.

The loss of political and social support for the Monarchy

The events that occurred throughout 1930 indicated that the return to the pre-1923 situation was not possible, because the Monarchy had become isolated. Sectors of society that had always supported the Monarchy, such as business owners, withdrew their support because they didn't trust its capacity to end the turmoil. The Monarchy also lacked the support of themiddle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

(the Church’s influence in this sector of society was being displaced by democratic and socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

ideas), and intellectuals and university students clearly publicized their rejection of the King.

One of the few groups that supported the Monarchy was the Catholic Church (which was fond of the Monarchy, as it reestablished its traditional position in society), but the Church was on the defensive due to the growth of republican and democratic ideals in the country. Another source of politica support for the Monarchy was the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, although some sectors of this institution were abandoning their support for the King. In the words of Juliá Santos, “Perhaps the Army in itself would never participate in a conspiracy against the Monarchy but neither would it do anything to save the throne, and there weren't few military personnel that hurriedly collaborated with the anti-monarchic conspirators”.

The prime of Republicanism and the Pact of San Sebastián

The social changes that had occurred in the previous thirty years did not help the reestablishment of the Restoration period's political system This reality, along with the public's association of the Dictatorship with the Monarchy, can explain the rapid growth of Republicanism in the cities. Thus, in this fast politization process, thelower

Lower may refer to:

*Lower (surname)

*Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

*Lower Wick Gloucestershire, England

See also

*Nizhny

Nizhny (russian: Ни́жний; masculine), Nizhnyaya (; feminine), or Nizhneye (russian: Ни́� ...

and middle urban classes were convinced that the Monarchy signified despotism

Despotism ( el, Δεσποτισμός, ''despotismós'') is a form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute power. Normally, that entity is an individual, the despot; but (as in an autocracy) societies which limit respect and ...

, and Democracy signified a Republic. According to Juliá Santos, in 1930, “the hostility against the Monarchy spread like an unstoppable hurricane in meetings and demonstrations throughout Spain”; “people began to cheerfully make for the streets, under any pretext, to praise the Republic”. The Republican cause also had the support of the intellectuals that formed the Group at the Service of the Republic, led by José Ortega y Gasset, Gregorio Marañón

Gregorio Marañón y Posadillo, OWL (19 May 1887 in Madrid – 27 March 1960 in Madrid) was a Spanish physician, scientist, historian, writer and philosopher. He married Dolores Moya in 1911, and they had four children (Carmen, Belén, María ...

and Ramón Pérez de Ayala

Ramón Pérez de Ayala y Fernández del Portal (9 August 1880, in Oviedo – 5 August 1962, in Madrid) was a Spanish writer. He was the Spanish ambassador to England in London (1931-1936) and voluntarily exiled himself to Argentina via Fr ...

).

On 17 August 1930, the Pact of San Sebastián The Pact of San Sebastián was a meeting led by Niceto Alcalá Zamora and Miguel Maura, which took place in San Sebastián, Spain on 17 August 1930. Representatives from practically all republican political movements in Spain at the time attended t ...

was signed in a meeting organized by Republican Alliance. Apparently, (as no written account of the meeting was produced) the parts agreed to follow a strategy that put an end to King Alfonso XIII’s Monarchy and proclaim the Second Spanish Republic. According to an official note, the following people and groups assisted the meeting: Republican Alliance; Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

of the Radical Republican Party

The Radical Republican Party ( es, Partido Republicano Radical), sometimes shortened to the Radical Party, was a Spanish Radical party in existence between 1908 and 1936. Beginning as a splinter from earlier Radical parties, it initially played a ...

, Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Repu ...

of Republican Action Group; Marcelino Domingo

Marcelino Domingo Sanjuán (26 April 1884 – 2 March 1939) was a Spanish teacher, journalist, and politician who served as a minister several times during the government of the Second Spanish Republic.

Biography

Early life & political career ...

, Álvaro de Albornoz

Álvaro de Albornoz y Liminiana (June 13, 1879, Asturias – October 22, 1954, Mexico) was a Spanish lawyer, writer, and one of the founders of the Second Republic of Spain.

Early life

He began his early studies in his native town of Luarca, ...

and Ángel Galarza

Ángel Galarza (1892–1966) was a Spanish lawyer, journalist and politician who served as the minister of interior in the period 1936–1937. He left Spain following the civil war for Mexico. In 1946 he settled in Paris, France.

Early life and ...

of the Radical Socialist Republican Party

Radical Socialist Republican Party (PRRS; es, Partido Republicano Radical Socialista), sometimes shortened to Radical Socialist Party (PRS; ''Partido Radical Socialista''), was a Spanish radical political party, created in 1929 after the split of ...

; Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and Miguel Maura of the Liberal Republican Right; Manuel Carrasco Formiguera

Manuel Carrasco i Formiguera (3 April 1890 – 9 April 1938), was a Spanish lawyer and Christian democracy, Christian democrat Catalan nationalist politician. His execution, by order of Francisco Franco, provoked protests from Catholic journ ...

of Catalan Action; Matías Mallol Bosch of Republican Action of Catalonia; Jaume Aiguader of Catalan State and Santiago Casares Quiroga of the Galician Republican Federation. The meeting was also individually assisted by Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

, Felipe Sánchez Román and Eduardo Ortega y Gasset

Eduardo Ortega y Gasset (1882–1965) was a Spanish politician, journalist and lawyer.

Biography

Born in Madrid on 11 April 1882. He was the older brother of philosopher José Ortega y Gasset.

He became a member of the Congress of Deputies af ...

, brother of José Ortega y Gasset. Gregorio Marañón could not assist the meeting but sent “an enthusiastic letter of adherence”.

In October 1930, the Pact was joined in Madrid by two socialist organizations, PSOE

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gov ...

and UGT, with the purpose of organizing a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

followed by a military insurrection that would cast the Monarchy into “the archives of History

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

”, as was said in the manifesto published in mid-December 1930. In order to coordinate the action, a “Revolutionary Committee” was formed, composed of Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, Miguel Maura, Alejandro Lerroux, Diego Martínez Barrio

Diego Martínez Barrio (25 November 1883, in Seville – 1 January 1962) was a Spanish politician during the Second Spanish Republic, Prime Minister of Spain between 9 October 1933 and 26 December 1933 and was briefly appointed again by Manuel ...

, Manuel Azaña, Marcelino Domingo, Álvaro de Albornoz, Santiago Casares Quiroga

Santiago Casares y Quiroga (8 May 1884, in A Coruña, Galicia – 17 February 1950, in Paris) was Prime Minister of Spain from 13 May to 19 July 1936.

Biography

Leader and founder of the Autonomous Galician Republican Organization (ORGA), a Ga ...

and Luis Nicolau d’Olwer, the nine representing the Republican faction, and Indalecio Prieto, Fernando de los Ríos

Fernando de los Ríos Urruti (8 December 1879 – 31 May 1949) was a Spanish professor of Political Law and Socialist politician who was in turn Minister of Justice, Minister of Education and Foreign Minister between 1931 and 1933 in the early yea ...

and Francisco Largo Caballero

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist. He was one of the historic leaders of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and of the Workers' General Union (UGT). In 1936 and 19 ...

, the three representing the Socialist faction. Meanwhile, the CNT continued reorganizing itself (although after the lifting of its ban it was only allowed to reconstitute itself at the provincial level) and, in accordance with its left-libertarian and “anti-political” program, did not participate in the republican-socialist alliance, and thus continued to act as a revolutionary leftist anti-establishment party.

The first failed attempt against the Monarchy

The Republican-Socialist Revolutionary Committee, presided by Alcalá-Zamora, which had its meetings at theAteneo de Madrid

The Ateneo de Madrid ("Athenæum of Madrid") is a private cultural institution located in the capital of Spain that was founded in 1835. Its full name is ''Ateneo Científico, Literario y Artístico de Madrid'' ("Scientific, Literary and Artistic ...

, orchestrated a military insurrection, supported in the streets by a general strike. The use of violence to achieve power and overthrow a regime had been legitimized by the preceding coup that brought the Dictatorship.Nevertheless, the general strike was never called, and the military proclamation failed because captains Fermín Galán and Ángel García Hernández initiated the revolt in the Jaca garrison on December 12, three days before the established date. These events are known as the “Jaca uprising

The Jaca uprising ( es, Sublevación de Jaca) was a military revolt on 12–13 December 1930 in Jaca, Huesca, Spain, with the purpose of overthrowing the monarchy of Spain.

The revolt was launched prematurely, was poorly organized and was quickly s ...

”, and the two insurgent captains were subjected to a summary military tribunal and executed. This mobilized public opinion in favor of the memory of the two “martyrs” of the yearned Republic.

Admiral Aznar’s government and the fall of the Monarchy

Despite the failure of the Revolutionary Committee’s efforts to bring about the Republic, and even though its members were either detained, in exile or in hiding, General Berenguer felt compelled to reestablish the validity of Article 13 of the 1876 Constitution, which recognized the public freedoms of expression andassociation

Association may refer to:

*Club (organization), an association of two or more people united by a common interest or goal

*Trade association, an organization founded and funded by businesses that operate in a specific industry

*Voluntary associatio ...

, and to call for general elections on 1 March 1931 with the objective of “constituting a Parliament which, along with the Courts of the last period rimo de Rivera’s dictatorship reestablishes the functioning of the co-sovereign forces in their entirety he King and the Courts as they are the axis of the Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy”. Thus, this was not a constituent assembly, nor was it an establishment of courts capable of reforming the Constitution. As a result, the announcement received no support, not even within the monarchists of the old Restoration parties.

Berenguer’s failure compelled Alfonso XIII to look for his replacement. On 11 February he called the Catalanist

Catalan nationalism is the ideology asserting that the Catalans are a distinct nation.

Intellectually, modern Catalan nationalism can be said to have commenced as a political philosophy in the unsuccessful attempts to establish a federal state i ...

leader Francesc Cambó

Francesc Cambó i Batlle (; 2 September 1876 – 30 April 1947) was a conservative Spanish politician from Catalonia, founder and leader of the autonomist party ''Lliga Regionalista''. He was a minister in several Spanish governments. He supported ...

to his Palace, having already become acquainted with him in a meeting in London the previous year.

On 13 February 1931 King Alfonso XIII ended General Berenguer’s dictablanda and named Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar new president. At the time Aznar was sardonically described as “from the Moon politically and , from Cartagena geographically”, due to his minor political importance. Alfonso XIII had previously offered the post to liberal Santiago Alba and the “constitutionalist” conservative

On 13 February 1931 King Alfonso XIII ended General Berenguer’s dictablanda and named Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar new president. At the time Aznar was sardonically described as “from the Moon politically and , from Cartagena geographically”, due to his minor political importance. Alfonso XIII had previously offered the post to liberal Santiago Alba and the “constitutionalist” conservative Rafael Sánchez Guerra

Rafael Sánchez Guerra (28 October 1897 – 2 April 1964) was a Spanish lawyer, journalist and politician who was the 8th president of Real Madrid from 31 May 1935 until 4 August 1936.

His presidency at Real Madrid coincided with the Spanish ...

, but both declined the nomination, with Sánchez Guerra having visited the imprisoned members of the Revolutionary Committee to ask them to join his Cabinet but receiving the refusal of all of them, with Miguel Maura telling him: “We have nothing to do or say about the Monarchy”. Aznar formed a government of “monarchical concentration” that was composed of leaders of the old liberal and conservative dynastic parties, as the King only accepted the presence of those who were “loyal to his person”, such as the Count of Romanones

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

, Manuel García Prieto

Manuel may refer to:

People

* Manuel (name)

* Manuel (Fawlty Towers), a fictional character from the sitcom ''Fawlty Towers''

* Charlie Manuel, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies

* Manuel I Komnenos, emperor of the Byzantine Empire

* M ...

, Gabriel Maura Gamazo son of Antonio Maura, and Gabino Bugallal. The Cabinet was also joined by a member of the Regionalist League

Regionalist League of Catalonia ( ca, Lliga Regionalista de Catalunya, ; 1901–1936) was a right wing political party of Catalonia, Spain. It had a Catalanist, conservative, and monarchic ideology. Notable members of the party were Enric Prat de l ...

, Joan Ventosa, with the objective, as Cambó explained a year later, of “obtaining for Catalonia’s cause what couldn’t be achieved until then”. For Santiago Alba, it was a government for the “palace serfdom”.: “let us not be fooled once again by the heir of Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

”, said Alba. The King trusted the government’s capacity to solve the situation, as Cambó certified in a personal meeting with him on 24 February: “I found him living in the best of worlds, oblivious to the weakness of the government, which was the base of his support”.

Aznar’s new government proposed a new electoral calendar: municipal elections would be held first on 12 April, followed by Court elections which would “have a Constituent character”, so that they could proceed to the “revision of the faculties of the State’s Powers and the precise delimitation of the area of each” (in other words, reducing the Crown’s prerogatives) and to “an adequate solution to the problem of Catalonia”.

On 20 March, during the electoral campaign, a drumhead court-martial

A drumhead court-martial is a court-martial held in the field to hear urgent charges of offences committed in action. The term sometimes has connotations of summary offence, summary justice.

The term is said to originate from the use of a drum as ...

against the Revolutionary Committee that orchestrated the failed civil-military movement was heard. The trial turned into a display of Republican will, and all of the accused were set free.

Everyone saw the 12 April 1931 municipal elections as a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

on the Monarchy. Therefore, when it became known that the republican-socialist candidacies had won in 41 of 50 province capitals, the Revolutionary Committee publicized an announcement stating that the election results had been “unfavorable to the Monarchy ndfavorable to the Republic”, and announced its intention to “act with energy and swiftness in order to give immediate effect to heaspirations f that majoritarian, longing and juvenile Spainby implementing the Republic”. On Tuesday 14 April, the Republic was proclaimed from the balconies of city halls that were occupied by the new councilors, and King Alfonso XIII was forced to leave the country. On the same day, the Revolutionary Committee turned into the First Provisional Government of the Second Spanish Republic.

References

{{Reflist Restoration (Spain) History of Spain Military dictatorships